Biden's new gas study is vulnerable to Trump. It could still be a useful tool in court.

Legal experts told Landmark that the findings of the study — which said expanded LNG exports could drive up costs and exacerbate climate change — could still be cited by environmental challengers.

In the waning days of presidential administrations, reports and studies like the one released by the U.S. Department of Energy this week warning of the potential dangers of liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports may seem somewhat pointless.

Republicans, for their part, said as much about the new report shortly after it came out Tuesday, believing President-elect Donald Trump will make good on his promise to deregulate American energy production once he takes office in just a few short weeks.

Their argument, in essence, is that the study won’t matter. Trump will soon toss it in the trash and give developers free rein to build export terminals to their heart’s desire. Industry attorneys appeared to largely agree, saying there are numerous flaws they could pick apart anyway.

But some legal experts said the study might still prove useful for groups that want to stop the expansion of LNG export infrastructure along the Gulf Coast and elsewhere, even if it ends up in the dump when Trump starts cleaning house.

That’s because the study and its data — which warn that unfettered LNG production and export could cause an increase in greenhouse gas emissions and raise domestic energy prices by over 30%, among other things — could still be used to show the harms of LNG in court.

In other words, it has created a record that can be easily cited and prove persuasive.

“The report could be very useful to those opponents if they are in front of a judge who already is inclined toward the opponent’s point of view or if the Trump administration simply ignores the report,” Keith Hall, the director of Louisiana State University’s Energy Law Center, told Landmark.

While the Trump administration could water down parts of the study that are critical of LNG development after receiving public comments, Hall said “the original report could still be of some use [to challengers] in litigation.”

Roots in the shale boom

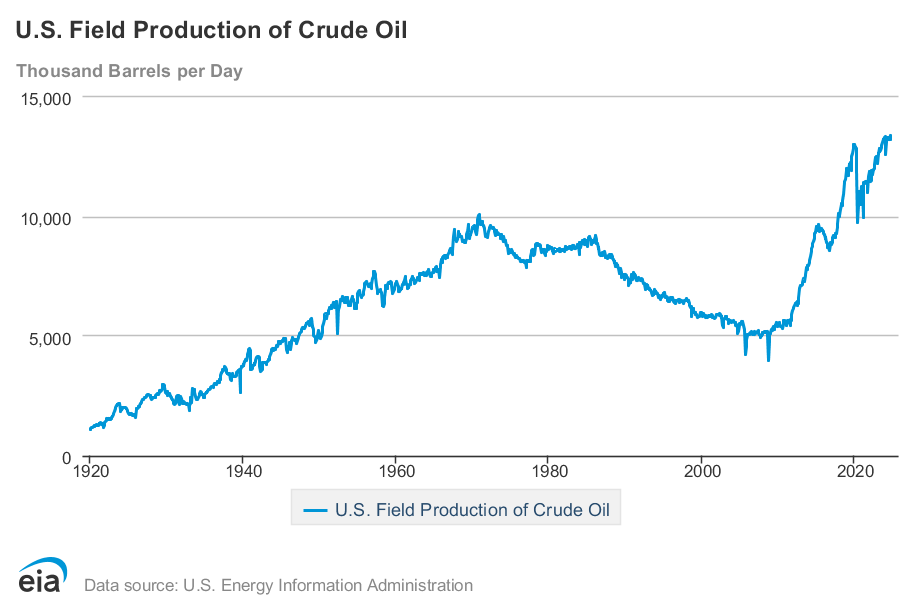

Interest in exporting LNG from American suppliers is a relatively new phenomenon, spurred by the growth in natural gas production that has occurred as a result of the U.S. shale boom that began in the mid-2000s and has continued to this day.

Prior to 2008, the United States was viewed as a growing importer of natural gas and was building LNG import terminals to meet that demand. But natural gas production in the U.S. spiked that year due to advances in methods of oil extraction called hydraulic fracturing, or fracking.

That process — in which a high pressure mixture of water, sand and chemicals are pumped into wells to crack shale rock and release oil and gas — unlocked fossil fuels from the ground that were otherwise too difficult to harvest.

A Congressional Research Service report released this year said that the shale boom has halved U.S. gas prices since 2008. Prices have remained stable since the U.S. started exporting LNG in larger quantities starting in 2016, though Russia’s invasion of Ukraine spurred spikes as European countries shunned Russian oil and looked to other suppliers.

U.S. LNG exports now rival those of Qatar and Australia, and have increased every year since 2016 when Cheniere Energy’s Sabine Pass facility opened in Sabine, Louisiana – marking the first such facility in the lower 48.

The expansion of LNG exports carries significant geopolitical implications. If the U.S. scales back its efforts, adversaries are likely to step in and supply countries like China with LNG, thereby limiting the American sphere of energy influence.

However, opponents argue that expanding LNG exports will release substantial amounts of greenhouse gases, further contributing to climate change. Experts warn that climate change can exacerbate costly flooding and droughts, heighten food and water insecurity, trigger mass migration or civil unrest, and potentially destabilize governments.

What’s in the public interest?

The growth of U.S. natural gas production and increased demand for LNG abroad has led to increased interest in building additional terminals that can put the commodity on ships, primarily in the Gulf of Mexico but also in other parts of the country like Alaska.

As of October, the DOE said over a dozen projects were under review for export approvals, including two in Louisiana’s Cameron Parish, Venture Global’s CP2 project and a Commonwealth LNG project.

Projects that have already been approved have been met with fierce legal fights, with groups arguing the projects are not within the public interest because they will cause disproportionate harm to minority groups in places like Cameron Parish or will spur long term greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change.

The DOE’s authority and responsibility to make the “public interest” determination comes via the Natural Gas Act, which largely left it to the executive branch to determine which exports to non-free-trade-agreement countries are consistent with the public interest. DOE - one of two leading agencies that approves LNG export terminals alongside the Federal Environmental Regulatory Commission, which permits construction itself – typically assesses variables including net economic impacts, security of domestic natural gas supply and environmental impacts.

(Note: The U.S. has comprehensive free trade agreements with just 18 countries, most of which are in South America. That means these authorizations are needed to ship gas to European countries as well as most Asian countries – huge markets due to Russian aggression in Ukraine and pressures to switch energy supplies in developing countries from coal to LNG to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.)

Fanning the litigation flames

The report issued Tuesday marks the culmination of a nearly year-long review that spurred legal challenges of its own by Republican attorneys general who claimed the DOE didn’t have authority to broadly stop issuing permits. (A Louisiana federal judge issued a preliminary injunction blocking the pause in July).

It was issued just as Trump is set to take office, where he has promised to accelerate investment in LNG and pledged to “approve the export terminals on my very first day back.”

Even before the report was released, though, there were warnings about being too hasty.

Ed Crooks of the analytics firm Wood Mackenzie, penned an op-ed essentially saying the report was doomed when Trump won the election, but said that rushing approvals could open the Trump administration up to the kinds of legal challenges that have already delayed projects in the past.

Scott Segal, a partner at the law firm Bracewell who represents energy industry clients, told Landmark he expects the Trump administration will withdraw the report “to remove any patina of authoritativeness it might have.”

He added that the report will now undergo a public notice and comment period, which will give interested parties the opportunity to question “some of the more obvious flaws in the document.”

“One thing that should not be tolerated would be the use of this report in future legal challenges on whether export approvals are in the public interest,” he said.

But challengers are likely to do so anyway.

Patrick Parenteau, a professor of law emeritus at the University of Vermont School of Law, told Landmark it would be a mistake for the incoming administration to simply ignore the report “and press ahead full throttle with LNG licensing” to achieve Trump’s “energy dominance” agenda.

“There will be litigation, and under the [Administrative Procedure Act], courts will take a hard look at whether the new administration has adequately explained why this report is wrong,” he said.

Tracy Carluccio, the deputy director of the environmental group the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, told Landmark meanwhile that Trump could try to pull back the report, but it could be difficult because “the facts are on the record and stand on their own when a decision is objectively examined.”

In other words: the Trump administration would have to have a good explanation for its changes, and the Biden administration “has dotted their i’s and crossed their t’s” in putting the study together, Carluccio said.

Moneen Nasmith, an attorney at the environmental law firm Earthjustice, which has frequently challenged LNG export approvals, suggested meanwhile that they will be watching closely.

“Any administration that adheres to science and facts and wants to protect American interest should be taking these findings seriously and prevent further expansion of export volumes,” Nasmith said. “The failure to do so will raise serious questions about the legality of any future approvals.”