The Supreme Court just dealt a big blow to a Biden pollution rule — here's what you need to know

The Biden administration's 'Good Neighbor' rule is loathed by red states and industry. In dissent, Justice Amy Coney Barrett called problems with the rule procedural

We have a quick post today to explain the U.S. Supreme Court’s Thursday decision in Ohio et al. v. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The opinion itself can be viewed on the court’s website here.

The U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday temporarily blocked a Biden administration plan to reduce smog-forming pollution that crosses state lines, marking the latest environmental law loss for the administration before the high court.

The 5-4 decision authored by conservative Justice Neil Gorsuch does not outright kill the rule issued under the Clean Air Act’s “Good Neighbor” provision. Instead, the decision pauses its implementation while a lower court reviews challenges filed by Republican-led states as well as the steel and fossil fuel industries.

But Gorsuch did write that the challengers are likely to succeed in that lower court fight on the merits, since the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency didn’t adequately explain the rule.

What is the Clean Air Act’s Good Neighbor rule?

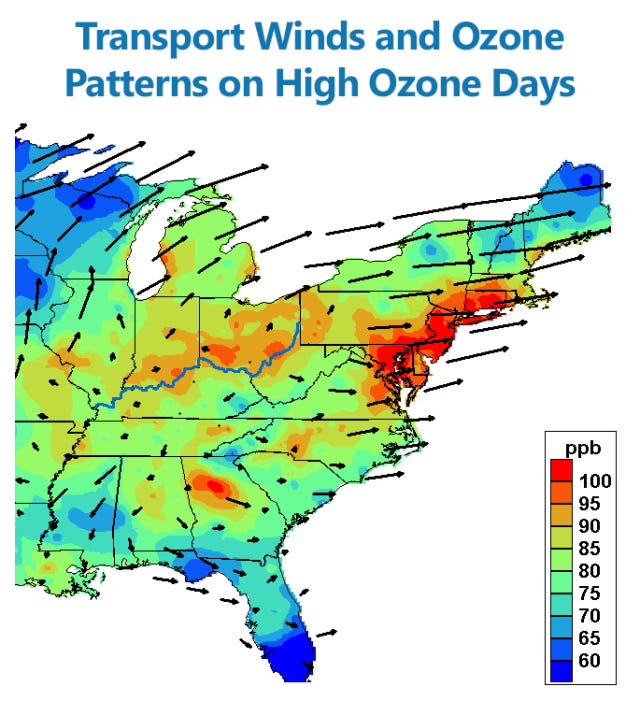

The Clean Air Act’s so-called Good Neighbor provision prohibits states from allowing their power plants and other industries to release emissions that significantly degrade air quality standards in downwind states.

In other words, if coal plants in Ohio, West Virginia or Indiana (the states that led the challenge before the Supreme Court) release emissions that are carried by wind into another state, making it harder for that state to meet air quality standards, they are required to control those emissions.

How big of a deal are the protections?

The EPA has said the now-blocked Good Neighbor rule will help save thousands of lives and help clean up the air for millions of others.

However, opponents argue that the rules will impose substantial costs on industry and could destabilize the electric grid, particularly for older and dirtier power plants trying to comply with the requirements while remaining profitable.

How is the provision implemented?

The Clean Air Act is structured around the principle of “cooperative federalism,” which means in this context that the EPA sets the emissions standards and the states themselves get the first crack at writing rules to comply with the standards.

The thinking is that states will have a better idea of how to control emissions to meet the standards while ensuring their industries can continue thriving. So, they submit what are known as State Implementation Plans (SIPs) to the EPA for approval. If the EPA says those plans aren’t good enough, states can initially rework them.

But if revisions continue to fall short, the EPA can eventually impose what’s known as a Federal Implementation Plan (FIP), which is what is at issue in the Supreme Court case decided on Thursday.

What is the FIP here?

The current fight has roots in the EPA’s 2015 decision to revise its air quality standards for ozone, which can cause lung damage and contributes to the formation of smog.

The EPA disapproved SIPs geared to comply with those standards for 23 states in 2022, and then crafted a FIP that would apply to all of them.

But several states and industry groups challenged the decision to disapprove the SIPs, and courts stayed the disapprovals in 12 of the 23 states. Since disapproval is key for a FIP to go forward, that means the FIP already does not apply to those 12 states.

What did each side argue in court?

The challengers have argued the FIP was written as an overarching rule and that the analysis supporting it rested on the assumption that it would apply to all 23 states. Developing a FIP requires complex modeling to balance the costs and benefits of reducing emissions from a variety of pollution sources, and removing states from the equation throws that balance out, they said.

Supporters of the rule have claimed meanwhile that the rule was drafted to stand up even if some states were removed. They have also argued the rule is well within the EPA’s statutory authority.

What did the justices say?

Gorsuch — joined by conservatives Chief Justice John Roberts, and Justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh — agreed with the challengers, finding the rule is likely arbitrary and capricious. The EPA didn’t have a good enough response to concerns that the rule’s analysis would shift if some states were removed, they said.

Conservative Justice Amy Coney Barrett — joined by liberal Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson — criticized the majority's decision in a dissent, arguing that it allows upwind states to continue contributing to ozone issues in downwind states due to what is likely just a procedural error.

“[T]he Court’s injunction leaves large swaths of upwind States free to keep contributing significantly to their downwind neighbors’ ozone problems for the next several years — even though the temporarily stayed SIP disapprovals may all be upheld and the FIP may yet cover all the original States,” Barrett wrote. “The Court justifies this decision based on an alleged procedural error that likely had no impact on the plan.”

What’s next?

The D.C. Circuit is overseeing the underlying case that went before the Supreme Court.